As in the reign of Philip II (see another article), Spanish ciphers in the seventeenth century included a class of ciphers called general ciphers, which were used by the King and his ministers in general. Hereinafter, numbers with a prefix Cg. refer to the numbering by Devos (1950) for general ciphers ("cifra general"). Similarly, numbers with Cp. refer to particular ciphers for use between particular persons.

One copy (Cg.47) of this cipher is titled a "general cipher" for ministers in Italy and another copy (Cp.59) is for ministers in Italy to correspond with the Constable of Castile (for which title, see Wikipedia); Don Juan Batista de Tassis, ambassador in France from 1599 to February 1604 and member of the Council of War from March 1604 (Devos p.48, 539); and ambassadors in Germany, France, and Flanders.

This cipher consists of the following elements.

(i) Cipher alphabet (symbols representing the letters of the alphabet). Each letter is assigned two to five symbols, which are mostly Arabic numerals 01-99, with a few exceptions.

(ii) Vowel indicators ("finales de vocales"), which are combined with symbols of the cipher alphabet to form syllables. For example, a vowel indicator for a is "+" and that for e is ":", while b is assigned "98" and "08" in the cipher alphabet. Thus, ba and be are represented by "98+" and "08:", etc.

(iii) Code for representing syllables, whereby two- or three-letter syllables are represented by two- or three letter codes or two-digit Arabic numerals.

(iv) Double letters, represented by signs like "++" or "tt" above a symbol in the cipher alphabet.

(v) Nulls (insignificant symbols). A hacek, a hat, ∞, an umlaut over a symbol and an underline indicate the symbol is a null.

(vi) A "2" over an Arabic figure indicates it literally means the number.

(vii) Nomenclature. List of codes consisting of one, two or three letters representing common names and words. A few are assigned non-alphabetic symbols or Arabic numerals.

This is a cipher for correspondence with ministers in Italy. Generally, this has a similar structure as Cp.59 (1604) above. The cipher alphabet consists of arbitrary symbols, substitute Latin letters, and Arabic numerals such as 91-99 and 301-310. Two- or three-letter syllables are represented by Arabic numerals 1-80, 100-104, 500-508 (some of which are with a hacek) or two-letter codes. The nomenclature assigns two- or three-letter codes or numerical codes 105-285 to common words and names.

This is a particular cipher with the Duke of Sessa, ambassador in Rome from 1590 to 1604. From the vocabulary of the nomenclature, Devos attributes this cipher to about 1600-1601. Cardinal Aldobrandino (code "z50") was sent in 1600 by the Pope to France with Matteo Argenti to reconcile Henry IV of France with the Duke of Savoy (resulting in Peace of Lyons in 1601).

Unlike Cg.47 (1604)/Cp.59 (1604) and Cp.58 (1604), the nomenclature of this cipher has a different structure from that of typical ciphers at the time. It has groups numbered 1 to 51, each containing twenty-two syllables, words, or names corresponding to the letters of the alphabet.

| Numero 1 | ... | Numero 32 | ||

| a | ac | a | aca | |

| b | ad | b | adelante | |

| c | al | c | agora | |

| d | am | d | alguno | |

| e | an | e | alla | |

| f | ar | f | alli | |

| g | as | g | amigo | |

| h | at | h | amistad | |

| i | a | i | año | |

| l | a | l | antes | |

| m | ba | m | aqui | |

| n | be | n | aquello | |

| o | bi | o | armada | |

| p | bo | p | armas | |

| q | bu | q | assi | |

| r | bal | r | assistencia | |

| s | bel | s | autoridad | |

| t | bil | t | aviso | |

| v | bol | v | aún | |

| x | bul | x | aunque | |

| y | bam | y | bastimento | |

| z | bem | z | bueno | |

Thus, bueno is enciphered as "z32." An overdot indicates change of the last vowel: buena.

Cp.57 does not employ a vowel indicator system characteristic of the Spanish ciphers at the time. Instead, syllables (and also single letters) are included in the nomenclature (Numero 1 - Numero 31).

A memoire of 1603 by the French codebreaker François Viète contains advice concerning "the latest ciphers of Spain" (Pesic p.27). The first three codes mentioned ("67" for "en", "e6y2v45" for "dom Cesar", "t7p22" for "Ferrari") appear to be very similar to those in Cp.57, which substitutes "b7" for "en", "f6" for "dom", "y2" for "ce", "r48" for "sar", "t7" for "fe", and "p22" for "ra".

This cipher was used as early as 1596 in a letter (with interlinear decipherment) from the Duke of Sessa to Philip II (BnF es. 336 (Gallica) f.81 (no.42)).

It is noted that, whether intensional or not, spacing between symbols is as if to mislead codebreakers.

One would transcribe the beginning lines as follows:

but, actually, this should be parsed as follows:

This is deciphered as:

In contrast to frequent change of general ciphers during the reign of Philip II, Cg.48 was used for fourteen years.

The cipher alphabet assigns each letter two to four symbols, which are mostly Arabic numerals but some are derived from Latin or Greek letters. Strokes are used to vary the symbol. Thus, "4" represents s, while "4" with a horizontal stroke crossing the bottom stroke represents a and "4" with a vertical stroke crossing the right-most stroke represents t. The letter K is placed after Z and de is assigned its own symbol like "++".

Double letters, nulls, and vowel indicators are defined.

Two-letter syllables are represented by three- or two-letter codes or Arabic numerals 21-28, 51-99, 105.

In the nomenclature, words and names are represented by one- to three-letter codes, arbitrary symbols, or numbers 100-144 with a hacek, 1-42 with an underline, and 200-411. Use of numbers over 100 had not been common in Spanish ciphers.

In 1598, Philip II had decided to marry his eldest daughter Isabella, Archduchess of Austria, to Archduke Albert, his nephew and Governor of the Netherlands, and ceded them the sovereignty of the Netherlands. The marriage took place in April 1599, after the death of Philip II.

Philippe de Croy, comte de Solre, member of the Council of State in Brussels, was one of the Netherlanders who attended the festivities at the Spanish court celebrating the wedding of Archduke Albert and Isabella in the spring of 1599 and were made knights of the Golden Fleece. (Conflicts of empires, p.9-10). He was sent to Madrid by the Archdukes in 1604 (Devos p.548). When the Spanish troops under Spinola reconquered Lingen from the Dutch in 1605, the town was placed under the command of Solre (Conflicts of empires, p.31).

Cp.60 is a cipher of Solre for use with the Duke of Lerma, a favorite of Philip III until his fall in 1618. The cipher alphabet assigns an Arabic numeral (1-9) or other symbol to each letter and four additional two-digit Arabic numerals (16-19, 50-65) to each vowel. The nomenclature includes some numerical codes (10-[15], 20-49) for some common words and names.

Devos dates this cipher at 1605, the year the Archdukes sent an ambassador to England after the peace of 1604.

The cipher alphabet assigns each letter two to four symbols, including Arabic numerals or variants thereof and a few Latin letters with diacritical marks. Two letter syllables are represented by three- or two-letter codes. The nomenclature represents common words and names with numbers 40-100 and Latin letter combinations, including one-, two-, three-letter combinations as well as longer strings such as "no se", "sino", "silo", "loque," etc.

This small cipher is for use with General Spinola. From the entry of "the Duke of Lerma" in the nomenclature, Devos dates this cipher between 1602, the year Spinola arrived in the Netherlands, and 1618, when the all-powerful Duke of Lerma was expelled from the court and Philip III announced that he would rule in person.

The cipher alphabet assigns each letter an Arabic numeral or a substitute letter and each vowel is assigned an additional symbol. The small nomenclature assigns a symbol or a capital letter to seventeen words (and ñ).

An accompanying instruction of the cipher describes pre-transposition, whereby the plaintext letters are reordered before enciphering. For example, the plaintext is transposed as follows:

El enemigo sale a campaña, resistilde.

eelenimogaselcamaapañristslied

(That is, after the first letter, the third letter is placed before the second letter, the fifth letter is placed before the fourth letter, and so on.)

This is a cipher for General Spinola (Wikipedia), who had made a vigorous campaign in the Palatinate at the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War in 1618 and, after the truce with the Dutch expired in 1621, in the Low Countries. The cipher alphabet consists of arbitrary symbols and the nomenclature includes numerical codes of seven elements.

A letter of 5 February 1627 partly in numerical cipher from Jean de Croy, Count of Solre (Wikipedia), to Wilhelm Verdugo can be seen in Fig. 9 (p.8) of Mírka (1-2/2013) in Crypto-World.

The Count of Chinchon (Wikipedia), viceroy of Peru from 1629 to 1639, used at least two, possibly three ciphers. (Villena p.326-339)

The first cipher represents single letters and two-letter syllables with numerical codes and a small nomenclature represents names and words with two- or three-letter codes, numerical codes 102-183, and a few symbols. This was reconstructed by Villena from letters of 1628 and 1629.

The second cipher represents single letters with numerical codes. Two-letter syllables are represented by two- or three-letter codes, Arabic numerals, or alphabet-like symbols. This variety is common with other Spanish ciphers at the time. The Arabic numerals have a diacritical mark above in order to distinguish them from those in the cipher alphabet. A small nomenclature represents names and words with numerical codes, three-letter codes, and a few symbols. This was reconstructed by Villena from letters from 1630 to 1635.

The fragment of a letter below shows such a mixed nature of the Spanish cipher at the time, including Arabic numerals ("10" having a diacritic sign above) representing letters or syllables, one-, two-, or three-letter codes representing syllables, and a numerical code "29" with a diacritical mark in the nomenclature.

In 1632, it was decided that the Council of State and the Board of War should communicate directly with the viceroys of New Spain and Peru, using a special code.

This is a copy of the new general cipher that came with a letter of Coloma. The date 1647 is consistent with the fact that the nomenclature includes Reyna Christianisima (code "rin") but not the King of France. Louis XIII had died in 1643 and the boy king Louis XIV was yet nine. The date 1647 also explains Munster ("145"), where peace negotiations were held for the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, and Don Juan de Austria ("iij"). John of Austria the Younger was sent to Naples in 1647 when he was eighteen.

If the date 1647 is accepted, "Coloma" would be someone other than Carlos Coloma (1566-1637) among the Colomas, a noble family with strong connections to the military (Wikipedia).

The cipher alphabet assigns each letter a substitute letter and an Arabic numeral (two for vowels). There is no k. The letter j, separate from i, is placed after z.

Signs for vowels, nulls, numerals, and double letters are defined.

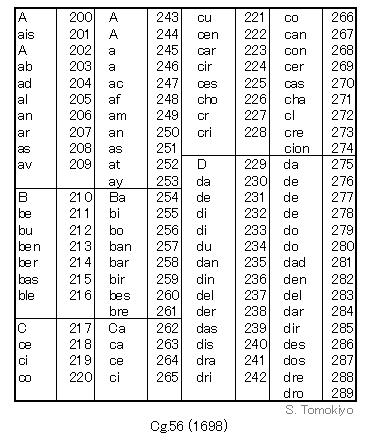

Two-letter syllables are represented by two-letter codes or numerical codes 25-61.

The nomenclature represents words and names with three-letter codes, symbols, and Arabic numerals 62-224.

The cipher alphabet assigns each letter two or three symbols (Arabic numerals or substitute Latin letters). There is no k. The letter j, separate from i, is placed after z.

Signs for vowels, nulls, numerals, and double letters are defined.

Two-letter syllables are represented by two-letter codes or numerical codes 45-84.

The nomenclature represents words and names with three-letter codes, single capital letters, a few symbols, and Arabic numerals 100-250. It still includes Reyna christianisima (code "222") instead of the King of France.

This is a cipher for the King to correspond with a Don Fernando de Faro. Devos dates this cipher at 1656-1659 from entries of the nomenclature Don Juan de Austria (260), Don Esteban de Gamarra (261), and Marques de Carazena (318).

When the Thirty Years' War ended with the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, France and Spain continued to be at war with each other and year after year, towns around the border between the Spanish Netherlands and northern France were taken and retaken. Don Juan of Austria was given command of the army in the Spanish Netherlands with Caracena, who succeeded him in 1659. Esteban de Gamara was ambassador in the Hague in 1656 (Devos p.359).

The cipher alphabet assigns three Arabic numerals to each letter. (The letter j, separate from i is placed after z.)

Signs for vowels, nulls, numerals, and double letters are defined.

Two-letter syllables are represented by numerical codes 100-194 or two-letter codes.

The nomenclature represents words and names by three-letter codes, Arabic numerals 200-421, and some arbitrary symbols. The term Rey de Francia is given a three-letter code "sin" and Principe de Oranje is given a code "pan." (Louis XIV started personal rule in 1661. At the time, his life-long rival Prince of Orange was yet a boy of ten.)

Villena (1954) describes three official codes from the latter half of the seventeenth century.

In 1658, it was decided to revive use of cipher. Since Cromwell's expedition to the West Indies in 1654, the risk of interception of letters to and from the New World had been great.

The official code of 1658 represents single letters with Arabic numerals or some symbols. Two- or three-letter syllables are represented by numerical codes or two-letter codes. The nomenclature represents names and words with numerical codes 101-200 or capital letters.

This cipher was sent to the viceroys of New Spain and Peru.

Spain made peace with France in November 1659 by the Peace of the Pyrenees and their ally Charles II was restored to the English throne in 1660. The Count of Alba de Liste, viceroy of Peru, felt less obliged to use the cipher.

When the situation in Europe became unstable again, it was decided to provide a fresh cipher to the viceroys of New Spain and Peru. No use of this cipher is known.

In 1675, a new cipher was sent to the viceroys of New Spain and Peru by the secretaries of the respective districts. Villena (1954) partially reconstructed the cipher from a dispatch from Lima in 1683.

The official code of 1675 represents single letters with Arabic numerals or some symbols. Two- or three-letter syllables are represented by two- or three-letter codes. The nomenclature represents names and words with numerical codes, three-letter codes, or symbols.

Spanish ciphers continued to use arbitrary symbols or letter codes as well as Arabic numerals in the mid-seventeenth century, while numerical code prevailed in Italy as early as the mid-sixteenth century and was common in England in the 1630s or earlier. The seeming difficulty of codebreaking provided by the variety of symbols is actually attainable by a pure numerical code.

This is a copy made in 1676 of a general cipher.

The cipher alphabet assigns each letter two or three symbols (Arabic numerals or substitute Latin letters). A symbol for k is not defined but "K" (as well as "tt") is used as a substitute letter for j, separate from i, placed after z.

Signs for vowels, nulls, numerals, and double letters are defined. Two letter syllables can be represented by Arabic numerals 40-84 or two-letter codes. The nomenclature represents words and names with two- or three-letter codes, single capital letters, a few symbols, and Arabic numerals 85-188. Although some symbols in the cipher alphabet have additional strokes, the nomenclature consists of only Latin letters and Arabic numerals rather than arbitrary symbols. It includes Rey de Francia (154) along with Rey christianisimo (158).

This consists of two nomenclatures. The first one consists of Arabic numerals 200-1011, representing proper names (200-371) and alphabetically ordered letters, common words, and names (375-1011). Examples are: Rey de España (913), Rey de Francia (914), and Rey de Inglaterra (916). The second one consists of Arabic numerals 100-924, representing three- or two-letter syllables as well as single letters and months. In order to distinguish the two series of numbers, the numbers of the first nomenclature should be marked with one of the letters a, b, c, [d], e, f over the code number. The numbers of the second nomenclature does not need to be marked or may be marked with one of the letters g, h, i, l, m, n over the code number. The letter o or p over the code number converts singular into plural or vice versa (e.g., hombre to hombres). The letter s or t over the code number converts male to female or vice versa (e.g., Duque to Duquesa). The letter v or x converts a noun into a verb or vice versa (e.g., impedir to impedimento).

These nomenclatures, covering single letters and syllables as well as common words and names, resemble general ciphers in the 1690s in that they use predominantly Arabic numerals.

Devos dates this cipher at 1675-1689 because the first nomenclature includes entries of the Marquis of Astorga, viceroy of Naples and former ambassador in Rome, and the Marquis of Carpio, ambassador in Rome and later viceroy of Naples.

This is a single nomenclature that represents single letters, syllables, names and words with Arabic numerals 1-999 and those preceded by θ. (Code numbers 299 and 307-999 preceded by θ and some other numbers are nulls.) Examples are: Su Mag. Christiana (970) and Su. Mag. Britanica (972).

Devos et al. (1967) prints a treatise (ca. 1676-1714) about deciphering found in the archives in Brussels (see another article). It is in French and was probably written by someone involved in Spanish deciphering activities in the Low Countries. One specimen in demonstration of deciphering involves the following cipher. This is somewhat similar to Cg.51 above.

The specimen is a portion of a report of the "success of 14 August" and reads: "Donde los hechos hablan de por si es ocioso al discurso ponderarlos y teniendo el presente tantas circunstancias que solo la admiracion puede celebrarlos dignamente no se gastaran en su narracion mas palabras de las que bastaren a referirlas." (p.70) (This text appears to refer to no specific event. One event of this date is the Battle of Saint-Denis (Wikipedia) in 1678 but it may not be called a success.)

In the 1670s or 1680s, it appears that a modern form of numerical code was adopted in the Spanish cipher tradition, whereby an integrated single nomenclature consisting of numeral codes covers single letters and syllables as well as common words and names. A disadvantage of such a numerical code is that, if sequential code numbers are assigned to alphabetically ordered elements, the regularity of the assignment may be exploited by codebreakers. This vulnerability is addressed by a so-called two-part code, which is said to have developed in France in the seventeenth century (Kahn p.161). Two-part code assigns code numbers to elements in random order and thus requires two separate sheets for enciphering and deciphering (i.e., one in alphabetical order and the other in numerical order). The Spanish ciphers in the 1690s were not two-part codes but used various means to hide the regularity without totally randomizing the assignment.

This is a single nomenclature that represents single letters, syllables, names and words with Arabic numerals 1-998 such as A (305, 315, 365, 375, 465, 485, 505), Rey Christianissimo (486), Rey de Inglaterra (526), Su Magestad Christianisima (196), and Su Magestad Britanica (206).

While many nomenclatures assign contiguous numbers to alphabetically ordered words, Cg.54 (1690) groups code numbers by ones place numbers. For example, a to Car are assigned numbers with a 5 in the ones place, car to de are assigned numbers with a 7 in the ones place, dexa to fa are assigned numbers with a 9 in the ones place, and so on. Such a structure somewhat obscures the regularity of assignment of code numbers, while still allowing the same encoding sheet to be used when decoding.

Again, this is a nomenclature that represents single letters, syllables, names and words with Arabic numerals 1-715 such as A (421, 481, 482, 541, 542, 661, 662), ab (362), Rey Christianisimo (152), Rey de Inglaterra (212), Su Magestad Christianisimo (280). Instead of assigning all the code numbers to words and names in alphabetical order, the code numbers are grouped into blocks having sixty entries: 1-60 (Ma-xan and nulls), 61-120 (Me-xo and nulls), 121-180 (Mi-yo and nulls), 181-240 (M-yu and nulls), ..., 361-420 (Ais-lleva etc.), and so on. As with Cg.54 (1690), the regularity of assignment of code numbers is somewhat obscured by this blockwise alphabetical structure.

As with Cg.54 (1690), this cipher groups code numbers by ones place numbers. For example, a to continua are assigned numbers with a 0 in the ones place, c to embargo are assigned numbers with a 9 in the ones place, and so on. Examples are: Rey Christianisimo (592), Rey de Inglaterra (602), Su Magestad Britanica (445).

This nomenclature assigns code numbers 1-468 and 645-666 to single letters, syllables, and nulls and 469-644 to words and names. Again, the first part of this nomenclature (codes 1-468) avoids a simple one-part structure without totally randomizing the assignment but in a different manner from that for Cg.54 and Cg.55. As seen in the image below, arrangement of numbers and that of letters/syllables are both fairly regular but they are different from each other, resulting in some mixing in the assignment. This can be seen as a variant of a two-dimensional sheet in which code numbers are arranged in one direction while words they represent are arranged in another direction. (For example, a cipher between John Barwick and Charles II and Edward Hyde (1659-1660) (see here) and Peterson's cipher and Manning's cipher (see here).)

This cipher is identical with Cg.51 above, a general cipher dating from a quarter century before.

This is for Baltasar Fuenmayor (d.1722), who was created the Marquis of Castel-Moncayo in 1682. He served as ambassador in Denmark, Holland, and Venice (Wikipedia).

In the eighteenth century, it appears numerical code was established in Spain, though two-part structure was not necessarily employed. A code of Governor of the Rio de la Plata (1717) (Villena TABLA I) is a two-part code, while its successor (1744) (Villena TABLA II) is a one-part code.

Devos, J. P. (1950), Les chiffres de Philippe II (1555-1598) et du Despacho universal durant le XVIIe siècle

Guillermo Lohmann Villena (1954), 'Cifras y Claves Indianas,' Anuario de Estudios Americanos, XI, p.285

Pesic, Peter (1997), 'François Viète, Father of Modern Cryptanalysis -- Two New Manuscripts', Cryptologia, 21:1, 1-29

List of Viceroys of Peru (Wikipedia)

List of Governors of the Rio de la Plata (Wikipedia)