Table of Contents

Ciphers between King Charles I and Prince Charles

Earl of Lauderdale and Countess of Carlisle (1648)

Towards Penruddock's Rising (1653-1655)

Towards Booth's Rising (1658-1659)

Towards Restoration (1659-1660)

Several cipher letters of King Charles I for Prince Charles, later Charles II, mentioned in another article, are briefly described below.

After the Battle of Naseby in June 1645, Charles I wrote letters in Lord Culpepper's cipher to Prince Charles, aged 15, who was striving to rally the royalists in the West. Those letters were deciphered by Culpepper and, after the Prince's perusal, were delivered again to him to be secretly kept. (Lord Culpepper, along with Edward Hyde, was the King's trusted friend appointed to attend the Prince of Wales.)

Shortly after the King was handed over to the English parliamentarians, the King wrote in cipher to the Prince in France on 3 February 1647, telling him not to come to England, upon any persuasion or threatening, before he sent for him. The letter was intercepted and was deciphered by John Wallis. A facsimile is printed in Geneva, Astrology and the Seventeenth Century Mind p.25, which allows partial reconstruction of the key as follows.

During the King's captivity, the Prince wrote on 17/27 March 1648 to Captain William Swan, desiring him to forbear declaring himself for him for the present till he could become master of the fort then commanded by Percival and enclosed his commission as Governor of Dover. Most of the letter is in cipher. The letters were represented by 10-12(y), 13-15(x), 16-18(w), ..., 76-78(a). Higher numbers represented words such as 79(although), 82(against), 83(at), 84(all), 85(and), 86(any), 89(command), 90(commission), 91(castle), 93(can), 94(could), 95(Dover), 97(do), 98(done), ..., 178(you), 179(your), 180(yet). (The manuscripts of His Grace the Duke of Portland, i, p.446-447, xxvii) (Dover was held by the parliamentarians, but in 1647, there were hostilities to the parliamentarian troops (The Dover Historian). It appears Royalist uprising did not materialize.)

During the captivity in the Isle of Wight, the King wrote the following cipher letters.

The reader is kindly asked to provide information if he/she knows or attains decipherment of these letters. (Note: In 2021, the latter two were solved by Norbert Biermann and Matthew Brown (see another article).)

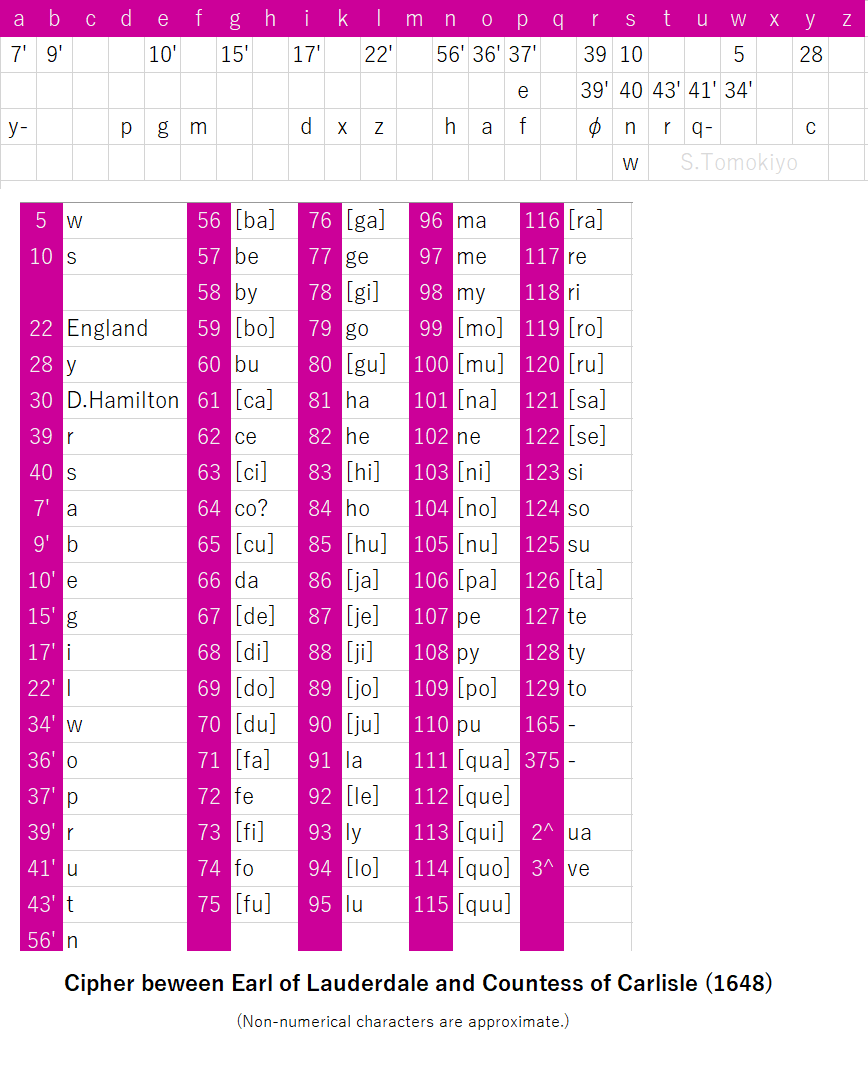

The cipher of a letter from the Earl of Lauderdale (Wikipedia) to the Countess of Carlisle (Wikipedia) dated (8 July 1648) was deciphered by John Wallis.

Lauderdale brought overtures from Scotland to Prince Charles in an interview in the Downs in August 1648 (where the prince came from Holland with a small royalist fleet with uncertain prospects of cooperation with royalists in England or releasing Charles I, then captive in the Isle of Wight) (Eva Scott, The King in Exile, p.54). Later, he accompanied the prince in his travel to Scotland and the subsequent expedition to England, and was taken prisoner at the Battle of Worcester in 1651.

The Countess of Carlisle helped the royalist cause, and was later imprisoned in the Tower of London, where she maintained a correspondence with Charles II through her brother, Lord Percy, before Charles went to Scotland.

The following is reconstructed from an image of a page deciphered by Wallis. The cipher with diacritics looks similar to those used in France at the time (see another article).

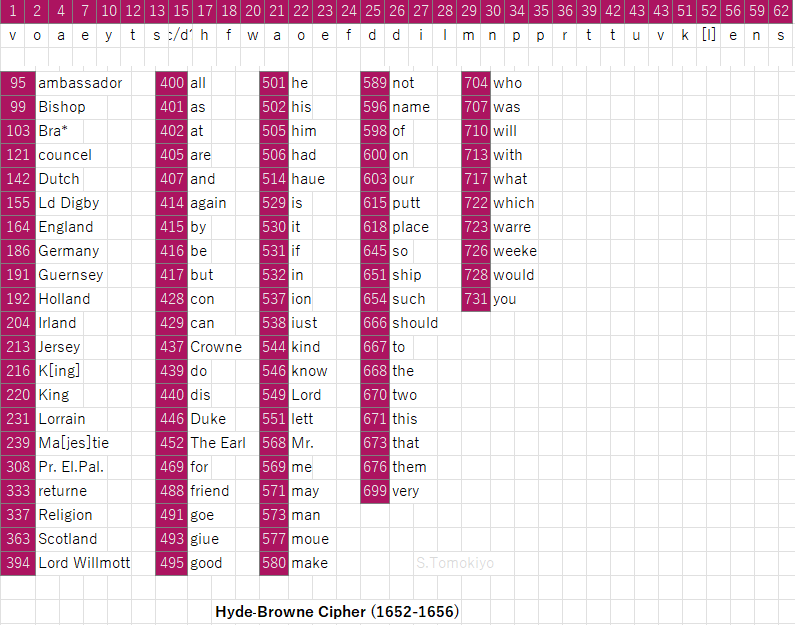

Letters from Edward Hyde to Sir Richard Browne, Royalist ambassador in France from 1641 to 1660 (Wikipedia), employs the following cipher.

The letters are printed in the appendix of Memoirs of John Evelyn, Esq. F.R.S., Vol. 5 (Google, p.248 ff.). (Evelyn was Browne's protegé and married his daughter (Wikipedia).)

The cipher is similar to the one used by Browne in 1643 ("Cipher for a Minister in Paris (1643)" in another article) in its irregular arrangement of single letters. (According to my notebook, Add MS 72438, ff. 70v-71r, no.125 is a cipher for "Mr Browne", but seems to be different from the above because it has numbers only up to 371. I cannot check this because the BL server is down due to a cyber-attack.)

While the deciphered letters are from 1652-1653, the reconstructed key above can read the short undeciphered text on p.333: 668 [the] 192 [Holland] 95 [ambassador].

The cipher used in a letter from John Bramhall, Bishop of Derry (then apparently in Flanders), to Ormond (1653) is reconstructed as follows (Calendar of the manuscripts of the Marquess of Ormonde, K.P., preserved at Kilkenny (Internet Archive, vol.1, p.293, footnote).

|

1-3 k 4-6 l 7-9 m 10-12 n 13-15 o 16-18 p 19-21 q 22-24 r 25-27 s 28-30 t 31-33 v 34-36 w 37-39 x 40-42 y 43-45 z |

49-51 a 52-54 b 55-57 c 58-60 d 61-63 e 64-66 f 67-69 g 70-72 h 73-75 i 44-46 are nils |

76 the King 86 Buckingham 89 Parliament 91 Independents 98 England 101 Ireland(?) 121 the Army 140 and 144 but 145 by 158 give(?) 166 have |

167 is 168 in 169 is(sic) 170 if 170 it(sic) 182 not 187 of 191 pay(?) 200 to 201 the 206 thought 209 what 211 when 215 yet(?) |

This cipher may have been the one received from George Lane, Ormond's secretary (ibid. p.117).

After the death of Charles I in January 1649, the Prince, who had been in France, assumed the royal title.

On 20/30 August 1649, Charles wrote to Sir Richard Fanshaw, then in Ireland under Ormonde, in Fanshaw's own cipher, directing him to join Cottington and Hyde, who were to be despatched to Spain to seek assistance from that court. (The Manuscripts of J. M. Heathcote, Esq., p.3, Internet Archive)

The following is a letter to request a loan to a recipient named in cipher.

Charles went to Scotland in June 1650 and was crowned there. But Charles was soon removed from the army ostensibly for the safety of his person but he suspected it was "for fear that he should get too great an interest with the soldiers." Though he was "narrowly watched", he managed to write to his friend the Duke of Hamilton.

To the dismay of young Charles, the covenanters in Scotland harassed Charles with demand after demand. Charles indignantly wrote to Edward Nicholas, then in The Hague, "nothing could have confirmed me more to the Church of England than being here seeing their hypocrisy" (3 September).

The cipher used in this letter uses not only figures but also a combination of an alphabetical letter and a figure. Such combination codes were also used in the second cipher between Charles I and Henrietta-Maria (Aug. 1642-Jul. 1643) and a cipher between Charles I and Prince Rupert (1644) (see another article) as well as Lord Digby, Lord Goring, and Lord Culpeper (see another article). Further, if the transcription in print (Evelyn's Memoirs) is to be trusted, two letter combinations such as "aq", "bb", "gg" and even single letters such as "h", "p" were used as part of the cipher.

Though it is hard to reconstruct the key from this letter, it seems numbers lower than 50 represent single letters (4[s], 7[y], 14[r], 30[a], 33[e], 34[g], 44[c]), higher numbers up to 200s represent generally alphabetically ordered words and syllables (138[have], 139[here], 141[I], 145[it], 147[is], 151[ing], 160[la], 169[ma], 170[me], 171[mo], 190[or], 242[to], 245[the], 262[with]), even higher numbers represent proper names (349[England], 575[Dule of York]), and letter-figure combinations also represent generally alphabetically ordered words and syllables (f5[here],g5[is],s3[re], w2[to], w5[the], x2[ve]).

On the very day that Charles wrote this letter, the covenanters were defeated by a much smaller force led by Cromwell at the Battle of Dunbar.

Exactly a year after the Battle of Dunbar, Charles was defeated at the Battle of Worcester in 1651 and barely fled to France.

The years following the defeat at Worcester were the nadir for the royalist cause. In 1653, Cromwell went so far as to dismiss the Rump Parliament by force in April and established a Protectorate in December. In 1654, because of rapprochement between Cromwellian England and France, Charles had to leave France to hold an exiled court in Cologne.

Some time between November 1653 and February 1654 (Underdown p.75, 76), when the conservatives were alarmed by development of the revolution, a Royalist secret association called the Sealed Knot was formed by royal appointment.

The cipher used in two letters from Charles II and Hyde to the agent "Symson" in May 1654 assigns numbers to letters of the alphabet as 1(e), 2(a), 3(r), ..., 12(e), ..., 20(e), ..., 53(s) (Underdown, Appendix A).

In the same period, pseudonyms were used among the King, Nocholas, Loughborough, Sir W. Compton, etc. at least from April to December 1654 (Underdown, Appendix C). There is another list of pseudonyms used among the King, Hyde, Nocholas, Ormonde, as well as members of the Sealed Knot (Belasyse, Compton, Russell, Villiers, Willys), etc. at least from May 1653 to October 1654 (Underdown, Appendix D).

The Sealed Knot was cautious about taking action and opposed to a premature attempt planned by an activist group of royalists.

In February 1655, Charles secretly left Cologne for Middelburg, Zealand, expecting a royalist rising in England (known as Penruddock's Rising), but, learning that a premature rising was easily suppressed, he returned to Cologne in April (Brett, Charles II and His Court, p.122).

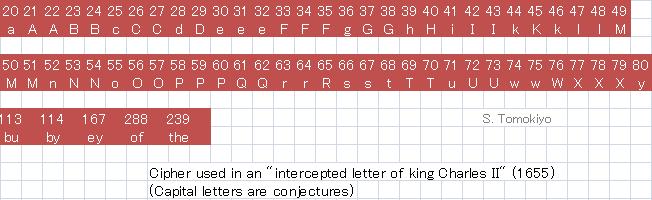

Thurloe State Papers records "an intercepted letter of king Charles II", dated Amsterdam, January 4, 1655 (NS) and signed J. Westrope, from this period (p.76).

Eric Sams and Julian Moore discovered a partial key to this cipher in 'Cryptanalysis and historical research' (1977). A little knowledge of the cipher at the time (see, e.g., another article) suggests that code numbers 20-80 represent single letters and three-digit codes represent words or syllables. They further assumed that the letters of the alphabet are assigned several consecutive numbers in alphabetical order. Such a regular cipher is actually seen in the case of the cipher used for Goffe's instructions (see another article) and the one between John Barwick, Charles II, and Hyde (see below).

Their feat of codebreaking with such a short ciphertext is impressive. They noted that the most frequent code numbers are in the low 30's and, focusing on the specimen "114 20 28 41 66 25 63 30 32 68 31 44 167", they assumed 30, 31, and 32 all represent "e". From the sequence "E E 68 E", they observed that "68=t" fits the context and is spaced from "e" by just about the right distance. The above specimen has two codes 63 and 66 near "68=t", which were supposed to be "r" and "s". Thus far, the above specimen was revealed to be "114 20 28 41 S 25 R E E T E 44 167", which suggests a word "discreete", which gives 28=d, 41=i, and 25=c. The placement of these numbers is consistent with the findings so far. From 25=c, 20 may be "a" and from 41=i, 44 may be "k". Thus, "k 167" would be "key", giving "167"="ey" and 114 would be "by" (rather than "in" or "with"), assuming the syllables are also in alphabetical order as was common in the ciphers used by Charles I.

This clue provided by Eric Sams and Julian Moore allows us to further recover some of the other assignments by interpolation as follows:

46 30 52 68 Kent

66 39 63 31 74 67 113 64 80 Shrewsbury

47 71 28 48 55 75 Ludlow

36 47 55 67 68 31 63 Gloster

239 41 67 48 32 288 31 47 80 the Isle of Ely

This allows conjectural reconstruction of the following key.

After writing the above, the present author noticed Underdown (p.347) prints a cipher with William Rumbold, which appears to be a short list of pseudonyms including "The King -- Westrope". A note "All by Mr. Roles" is attached to the names other than the King, Lord Lieutenant [Ormonde], Hyde, and Rumbold. The pseudonyms of the list were used in letters of the King, Hyde, and Rumbold from 24 October 1654 (OS) to 8 February 1655. The above letter had been known to historians by Calendar of the Clarendon State Papers (1876), iii (Internet Archive), p.3-4. Its text is a gist of a copy by Hyde and appears to be more or less different from the above in place names mentioned and does not mention the place of dispatch "Amsterdam" (apparently in disguise). It is a reply to the Knot's negative outlook to a rising planned by an activist group of the royalist party (cf. Underdown p.129).

The failure of the insurrection of March 1655 put the royalists' activities in disintegration. Royalists, even those not involved in the issurrection, were arrested (Underdown, p.159, 164). Cromwell introduced the Rule of Major-Generals and a new discriminatory 10% income tax known as "decimation tax" was imposed on royalists to finance militia, which was allegedly necessitated by royalist conspiracies (British Civil Wars, Commonwealth website).

On the bright side, Charles II secured an alliance with Spain in April 1656 and moved his court to Bruges. He also began recruiting exiles in Flanders. In England, a popular cry of "No Swordsman! No Decimator!" during the summer elections in 1656 led to abandonment of the system the following spring (Underdown p.178).

The Knot resumed its meeting near the end of 1656 (Underdown, p.201, 188) but was as inefficient as ever. Instead, a new action party was formed from an uncoordinated series of local conspiracies. (ibid. p.203). While the new action party was led by new men (ibid. 201), John Weston, one of the leaders from the 1655 rising, was active with notable enthusiasm (ibid. p.208).

The cipher used in a letter from Weston to the King of 30 August 1657 assigns numbers to letters of the alphabet as 5(m), 6(s), 7(s), ..., 10(h), 11(h), ..., 25(p), 26(p), ..., 34(t), 35(t), 36(t), ..., 97(e) (Underdown, Appendix B).

In the same period, a cipher endorsed "Cipher wth Mr. 9(c) 39(o) 40(o) 44(p) 14(e) 49(r)" is a list of pseudonyms and used in letters among John Cooper, Nicholas Armorer, and Ormonde in April-May 1656 (Underdown, Appendix F). The figure cipher used in the endorsement appears to be the same as the cipher between John Barwick, Charles II, and Edward Hyde (see below).

Another list of pseudonyms was used in letters from John Skelton to Hyde in November 1656 (Underdown, Appendix G).

At the end of 1657, the Spaniards were showing unusual willingness to cooperate with the royalists, though supporting activities in England were far from ready (Underdown p.215). In order to check the conditions, Ormonde was secretly sent to London in January 1658. His visit was detected by the spymaster Thurloe and the nine days of his stay in England were full of narrow escapes as well as consultations with the royalists (Underdown p.216).

During his stay, the Parliament's protestation against Cromwell's power resulted in dissolution of the Parliament by Cromwell on 4 February 1658. Seeing no favorable outcomes forthcoming, Ormonde left for France.

Ormonde's report was not pessimistic but told that the King's landing was necessary before any action would be taken by the royalists at home. This brought to the fore the fundamental impasse: the Spaniards required that royalists in England should first secure a port before any invasion, while the royalists required landing first. When the English fleet, temporarily driven off by weather, returned to the blockade of Ostend at the end of February, the scheme was called off (Underdown p.218-219)

In 1658, T. Kingston in Paris provided intelligence to Lawrence at the exiled court at Bruges. For example, he reported about Ormonde's journey, who had been discovered in his secret visit to London in January and fled to Paris before returning to Bruges by a circuitous route via Lyons and Bruges. In a letter of 22 February NS, he reported, among others, that Cromwell was ready to make peace with Spain and included his advice about a remedy of gout for Chancellor Hyde.

The cipher (THE=403) used in Kingston's letters represents single letters by lower numbers as below and higher numbers represent words and syllables in generally alphabetical order such as 40(ab), 43(and), 403(the), and 448(zeale).

Kingston's letters of April 1660, reporting that Lord Jermyn was certain that the King would be called to England, used a different cipher (THE=363). Words and syllables are included in four series of generally alphabetical entries such as 109(am)-194(you), 198(ar)-285(y), 290(are)-459(what), and 465(answer)-547(whom). There are further higher numbers such as 590/593(Lord Jermyn), 594/595(king), 622(restore), 644(Lord Aubigny), 857(Lord Chancellor), and 925(com. de Souvray/Souvres).

The archenemy Oliver Cromwell died in September 1658 but it did not bring about any favorable opportunity for royalists, with Richard Cromwell, Oliver's son, succeeding to the protectorship peaceably. On the other hand, after Ormonde's visit to London in early 1658, contacts were being made with Presbyterians (Underdown p.231, 223, 225).

In the Parliament that convened in January 1659, more than a score of royalists were represented and, together with Presbyterians, had a significant strength. Their basic strategy was to attack the Protectorate on general constitutional issues rather than hold up the royalist cause openly. Public opposition to the arbitrary government led to release of royalist prisoners. (Underdown p.233-234)

In March 1659, Mordaunt received the King's commission. Though received with suspicion by the indolent members of the Sealed Knot, he formed a new group with Presbyterians. They were even empowered to offer pardon and rewards as they deem appropriate to former rebels (regicides excepted). (Underdown p.235-238).

In April 1659, Richard Cromwell was deposed by officers of the army and the Rump Parliament was reinstaed in May.

Mordaunt's group acted energetically but could not obtain support of the Sealed Knot and other great lords. The insurrection in August 1659 ended in a predictable failure. The only rising that materialized, that of Sir George Booth (hence, the name Booth's Rising), was quickly suppressed by General Lambert.

After the failure of Booth's Rising, even Mordaunt had to concede to Hyde's opinion that no insurrection would succeed without support of troops from abroad (Underdown p.293 etc.).

In the summer of 1659, Charles was preparing to act in concert with the royalist insurrections in England. When he knew of Booth's defeat, however, he immediately repaired to the Pyrenees, accompanied only by Ormonde and a few others. Spain and France were negotiating for peace in a frontier town Fuenterrabia in the Pyrenees and he hoped the two monarchs might make some provision in the treaty to assist him.

On 8/18 October, Nicholas in Brussels wrote to Charles that Lord Mordaunt, with whom he kept correspondence in cipher, brought back from England a proposal of a match for the King's brother, the Duke of York, with a daughter of a general in power (no other than Lambert, who had successfully suppressed Booth's Rising). Nicholas enclosed this letter in one to Ormonde and enciphered it with Ormonde's cipher (Cal. SP, p.246). Nicholas felt use of cipher was indispensable because "your and our letters to and from these parts are all intercepted and opened by Lockhart," England's ambassador to France and governor of Dunkirk (ibid. p.255-256).

At the time, Lambert's power was such that he turned out the members of the Rump Parliament but it did not last. The proposed match came to nothing.

Alarmed of impending anarchy, General Monck, commander-in-chief of the English army in Scotland, declared for authority of Paliament and restored the Rump and then, in February 1660, the Long Parliament by readmitting the MPs excluded by Pride's Purge in 1648.

Soon the Long Parliament dissolved itself to give way to the Convention Parliament, which invited the King to resume the throne of England.

In February 1660, it was discovered that letters of royalists such as Rumbold and Mordaunt were intercepted and deciphered by John Wallis (see another article). Although Hyde did not at first believe the cipher could be broken, he had some inconvenience in communications.

On this occasion, the arrogant and tactless Mordaunt alienated himself from Hyde by groundlessly accusing his rival Brodrick for selling Rumbold's cipher. In reply, Hyde pointed out that Rumbold's was not the only cipher broken (Underdown p.301). (Hyde's hostility may have been exacerbated by Mordaunt's closer relations with the Louvre faction (Queen Henrietta-Maria, Jermyn, etc.). In December 1659, Jermyn even provided him with a cipher (Underdown p.303).)

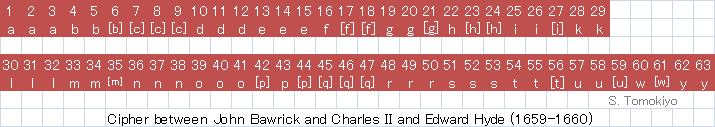

John Barwick was a royalist churchman. During the Civil War, as a chaplain to Thomas Morton, Bishop of Durham, he could manage royalist correspondence and intelligence work relatively covertly at Durham House, the Bishop of Durham's London residence.

Even when Charles I was kept at Carisbrooke Castle in the Isle of Wight, the King had the assistance of his servant Francis Cresset to lodge a cipher with Barwick and thereafter sent his commands written with his own hand in cipher. (Life of Dr. John Barwick, p.40, 157).

When a fellow royalist, Thomas Holder, Auditor-General of the Duke of York was arrested, he ventured to talk with him in prison and by his directions, found and burnt his ciphers and other papers (Life of Dr. John Barwick, p.43-44).

After Charles I was executed in January 1649, he continued daily correspondence with the King's ministers in exile and the new King Charles II (Life of Dr. John Barwick, p.53-54).

Though Barwick had successfully managed secret activities for eight years, he was at last detected. Betrayed by a post-office official named Bostok, parliamentarian officers broke into his room. Barwick barely managed to burn his ciphers and other papers. Thus, the parliamentarians could not make sense of the letters in cipher which fell into their hands through Bostock. (Life of Dr. John Barwick, p.57-58)

He was imprisoned in April 1650 but was released in August 1652. Later, he renewed his management of the king's correspondence. (Wikipedia, Life of Dr. John Barwick)

Thurloe State Papers as well as Life of Dr. John Barwick prints Barwick's correspondence with Charles II and Chancellor Hyde from September 1658 (when Cromwell died). Barwick not only reported the situation in England but had the King's letters delivered to parliamentarian generals. Barwick was the foremost among the royalists in England in collecting funds as well as winning over Army men (Underdown p.299, 308).

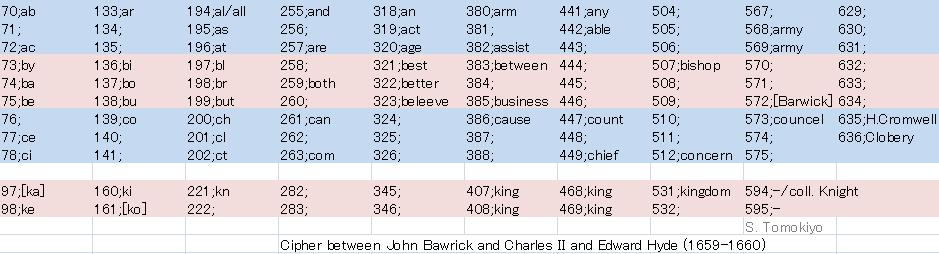

The cipher (THE=370) used in their correspondence represents single letters by numbers 1-63. The cipher was provided by Hyde: "Being assured ... that you have already received my Cypher" (Hyde to B[arwick], Brussels, 27 June 1659).

Higher numbers represent syllables and words, which consists of nine or ten alphabetical sequences of 61 to 63 entries such as 70(ab)-131(your), 133(ar)-193(will), .... When the entries are formed into a table, it is clear that the cipher was created by preparing a sheet with nine or ten columns; assigning each letter of the alphabet three (or two) rows; and filling the entries with syllables and words. It is noted that a few important words are assigned more than one code numbers: 568/569(army), 407/408/468/469(king).

Thus, though at first glance the words and syllables are assigned random code numbers, this is actually not a two-part code in the true sense (i.e., separate encoding and decoding sheets). This kind of tabular cipher with the appearance of random ordering is also seen in Peterson's cipher and Manning's cipher (see another article).

(By the way, Fletcher Pratt describes the cipher used by Charles II while in exile in Secret and Urgent: "It was an elaborate syllabic cipher, in which 70 was ab, 71, ad, 72, ac and so on, while very common words had special code numbers, 407, 408, 468 and 469 all being the king." Although he does not disclose his source, it is now clear that he referred to this cipher for Barwick.)

[notes added on 20 October 2012] After writing the above, I found the above cipher was described in the unabridged Life of Dr. John Barwick, p.408. The cipher was enclosed in Hyde's letter of 12 June 1659. The cipher consists of numbers from 1 to 692 in eleven columns on a sheet of paper. The first column extends from 1 to 63 for the letters of the alphabet and (with 64-69 skipped) the remaining ten columns are for syllables and words. It illustrates a porion of the cipher below.

[notes added on 23 October 2012] Soon after writing the above, I was taught by Davys, An essay on the art of decyphering, that a full cipher can be found in the Latin edition (next to p.316). Although the scan on Google is defecitve, it is enough for confirming the multiple typos of the English edition.

When the Convention Parliament proclaimed Charles king in the spring of 1660, Barwick was sent to the court at Breda by the bishops to report the state of the church. He preached before the King in a Sunday service and was afterwards made one of the King's chaplains (Life of Dr. John Barwick, p.150).

Some letters by Hyde have superscription in cipher (Superscriptions are printed in the Latin edition of Life of Barwick, but omitted in the English version.).

Examples of superscription in clear in the same volume are "For Mr. Brookes" (p.313 in Latin edition), "For Mr. B" (p.335), "For Mr. Burges, these" (p.339), "For the Lord General Monk" (p.441), "For General Monk" (p.442). The undeciphered superscription will also indicate recipients. 729 may be "for."

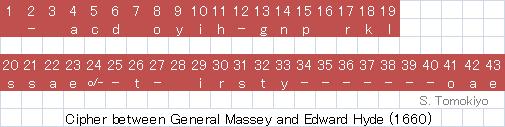

Chancellor Hyde also received cipher letters from General Massey in England. Massey was one of those excluded by Pride's Purge in 1648 and abhorrence of the execution of the King in 1649 made him turn to the royalist cause. In 1659, he was one of those who plotted a series of royalist revolts in England, which failed even before hardly taking place except for Booth's Rising. In 1660, he went to England again and was elected for the Convention Parliament in March (British Civil Wars, Commonwealth and Protectorate). While restoration seemed probable, the situation was yet volatile such that, as he was on his way to dine with the mayor, his life was threatened by inferior officers of the garrison with drawn swords (Davies, The Restoration of Charles II, p.327).

Massey's cipher uses lower numbers to represent single letters and nulls. Numbers higher than about 50 represent words and syllables in roughly alphabetical order such as 56(assist), 787/806(the), 853(zeal) and some additional words such as 859(one), 860(two).

Original Letters, Illustrative of English History: To 1726 (Google)

A vindication of King Charles the Martyr (1711), p.140 ff. Appendix (Google)

An account of the preservation of King Charles II after the Battle of Worcester (Google)

Memoirs of John Evelyn, Esq. F.R.S., Vol. 5 (Google)

John Albin, A New, Correct, and Much-improved History of the Isle of Wight (1795) (Google)

Thurloe State Papers (British History Online)

Manuscripts of His Grace the Duke of Portland, Vol. I (Internet Archive)

Eric Sams and Julian Moore, Cryptanalysis and historical research, 1977

Peter Barwick, Life of Dr. John Barwick, translated from Latin by Hilkiath Bedford and abridged/edited by G. F. Barwick (Internet Archive); an unabridged edition is found at Google; the Latin edition (Vita Johannis Barwick) is also on Google

Underdown, Royalist Conspiracy in England (1960)

Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series (Internet Archive)